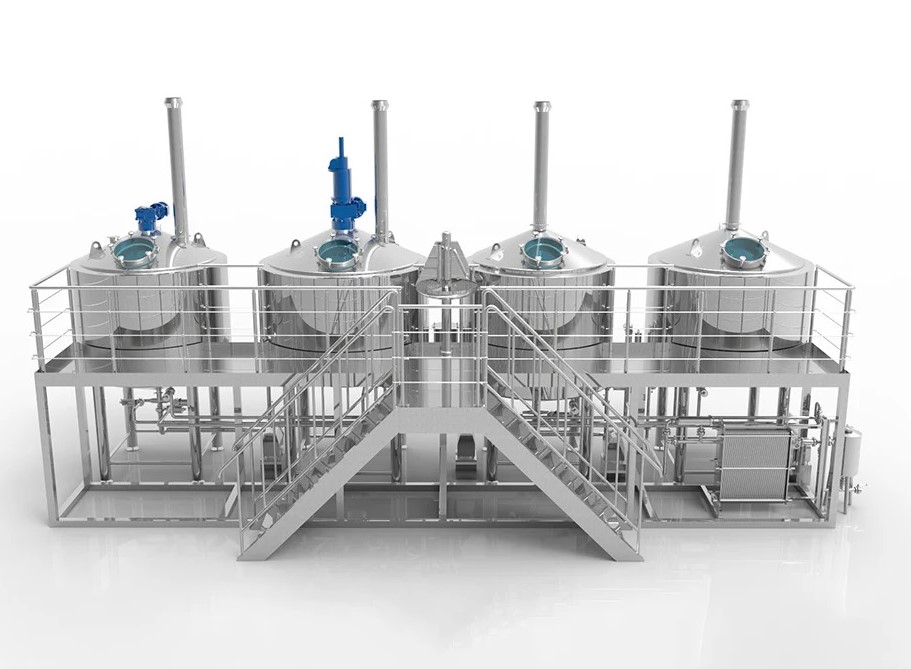

The mash system is one of the most important steps in a brewery. As we all know, mashing is the process of steeping crushed malt in hot water, resulting in the conversion of the starches in the malt into simple sugars. Using authentic mashing techniques for a specific beer style will improve the flavor, clarity and character of the finished beer. In this article, we will discuss the infusion mashing and decoction types of the mashing system together.

Single infusion mashed

The one-step brew mash is the bread and butter of 90% of the world’s whole-grain brewers. A single-step soak involves mixing a single pass of water at a temperature such that the target soak temperature (usually 148-158°F) is achieved in one step. After adding water, the mash is left in an insulated container for 30-90 minutes before being jetted to produce a sweet wort for brewing.

Advantage

Using modern malts, almost every beer style in the world can be replicated with a single infusion mash. With software and a little practice, the infusion temperature for any target temperature can be calculated. Minimal equipment is required – usually, an insulated water cooler can serve as the mash tun and lauter tun.

Soup saccharification

Bouillon mashing is a continental process developed before accurate thermometers were available. Instead of adding water at a fixed temperature, a part of the mash is taken at each step and boiled to raise the temperature of the mash for the next step.

Stock gelatinization may involve many cycles of separating stock, boiling, and returning to gelatinization. The traditional way to make a roux is a triple roux where the roux is boiled and returned to the main mash three times. So, there are four temperature breaks, one at which the grains are mashed and another after each decoction. Soup mash was developed before the thermometer, and the standard triple roux owes many of its functions to this fact.

Temperature saccharification

Temperature mashing involves applying direct heat to the mash tun to raise and maintain the temperature required for mashing. This method is used by many commercial breweries where they have precise control over the mash vessel.

Homebrewers rarely use this technique because it is difficult to maintain the temperature of the cauldron over the burner, and heating the insulated mash tun requires more than a simple plastic water cooler. If you can raise and maintain the temperature in the mash tun with some precision, temperature mashing is an acceptable alternative.

Other decoction procedures

Shorter decoction pastes exist, both double and single. By varying the size of the broth you extract and the temperature you mix it in, you can come up with any rest you want. If you mash in your kettle, you can also combine direct heat for steps or ramps within your decoction mash.

Mashup steps

After choosing a mash method, you need to determine the number of steps in your mash profile. But, in some cases, many steps need to be taken.

Below is a typical range of commonly used saccharification steps and their uses:

Acid and Dextran Rest

Breaks down the colloidal solids (glucose) and lowers the pH of the mash to form unmodified malt. The main benefit of acid residue is that it lowers the pH of the mash, which has many benefits for the finished beer. Modern improved malts rarely must glucan rest. Beers with very high levels of unmalted ingredients, such as unmalted barley, unmalted wheat, or oatmeal (> 25%), can be rested at 98-113F for 20 minutes to reduce the possibility of mash sticking.

Protein residue

Protein leftovers help break down long protein and amino acid chains into smaller chains needed for the glycation process. In unmodified malts, this will help head retention, reduce haze, and enhance malt flavor. But, modified malts do not enjoy protein rest.

Saccharification

The main event and the critical step is the brewhouse step. In this step, long sugar chains are broken down into smaller sugar chains that can be fermented by yeast. If you mash at a higher temperature for a shorter time, you’ll end up with a sweeter, malty, higher-bodied beer. Whereas mashing for longer at lower temperatures results in a thinner, cleaner, lighter-bodied beer. These are listed as full sugar, medium sugar, and light sugar body profiles corresponding to different sacrifice temperatures.

To choose to mash or not to mash steps?

A “mashing” step is usually added at the end of the mashing process, even for single steep mashing. In the mash, add more hot water or heat to raise the temperature of the mash to around 170 F. This blocks the action of most enzymes and also helps to thin the mash flow to prevent the mash from sticking.

The merits of the mashing step are much debated in winemaking circles. Many brewers skip the mashing process with no ill consequences. Adding mash is generally recommended only if you’re brewing beer with a lot of wheat, unmalted barley, or other additives that can cause the mash to stick. Stopping the action of the enzymes is not that important, since most brewers strain it into the boiler, and the wort will boil pretty quickly anyway.